Infective Maltruism: Is Charity Still Charity When It Is Performed for Uncharitable Reasons?

Looking beyond the “aw, neat, what a great person” façade of effective altruism, one clearly finds a level of narcissistic cynicism and a drive to the permanent power that financial immortality affords that is only matched by the amount of funds being dispersed.

The gifts offered by today’s billionaires—the Silicon Valley crowd, et al.—sound great (-ish—very -ish), but to discount the obvious underlying reason is to fail to grasp the insidious nature of their beneficence.

In the past, the rich tended to fund things—museums, schools, libraries, parks—when they gave their money away. These things were meant to accomplish two goals: to keep the benefactors’ names alive so future generations would “look them up” and to generally uplift society. Museums were given to the masses not as a monolithic lump, but as discrete individuals who could choose—except for fourth graders on field trips—to take advantage of them or not.

But effective altruism eschews such methods, focusing on causes and organizations—organizations that can be controlled indefinitely by controlling the flow of funds—in an effort to exert current and future societal control. Joining the Silicon Valley obsession with physical immortality is now the idea of financial—and therefore sociopolitical—immortality.

The creation of philanthropic LLCs to divvy up tech and other zillionaire dollars perpetuates the “lives” of donors by allowing them to forever control politics, policies, and culture. This control also becomes a form of eternal nepotism, as it has the side benefit of really, really helping donors’ individual descendants keep at the center of power and finance (the “Smith Initiative” will always hire a Smith and will always have a Smith on its board).

A key aspect of this “maltruism” is its ability to extend control through soft-sounding enterprises. How can something with “open” and “democracy” and “save” in its name—and a nonpartisan, nonprofit entity to boot—be anything but good?

As to philanthropic LLCs, they are seemingly the preferred way of doing the charity business of our current (and, they hope, forever) overlords. In a nutshell, they are not traditional charities, but organizations that can mix for-profit and nonprofit activities under the same umbrella. For example, in theory, by making money investing in x, you can give more money to y.

Even better, you can decide whether or not to leave your profits in the “charity,” enjoy certain (admittedly limited) tax benefits, and—unlike regular charities—you don’t really have to tell anyone where the money comes from or, more importantly, where it is going.

Better still, you can do something charities really can’t: play politics. Such LLCs are legally entitled to engage in political activities like advocacy, lobbying, and, in the case of Silicon Valley’s own Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI), significantly impact present-day elections (a very big more better).

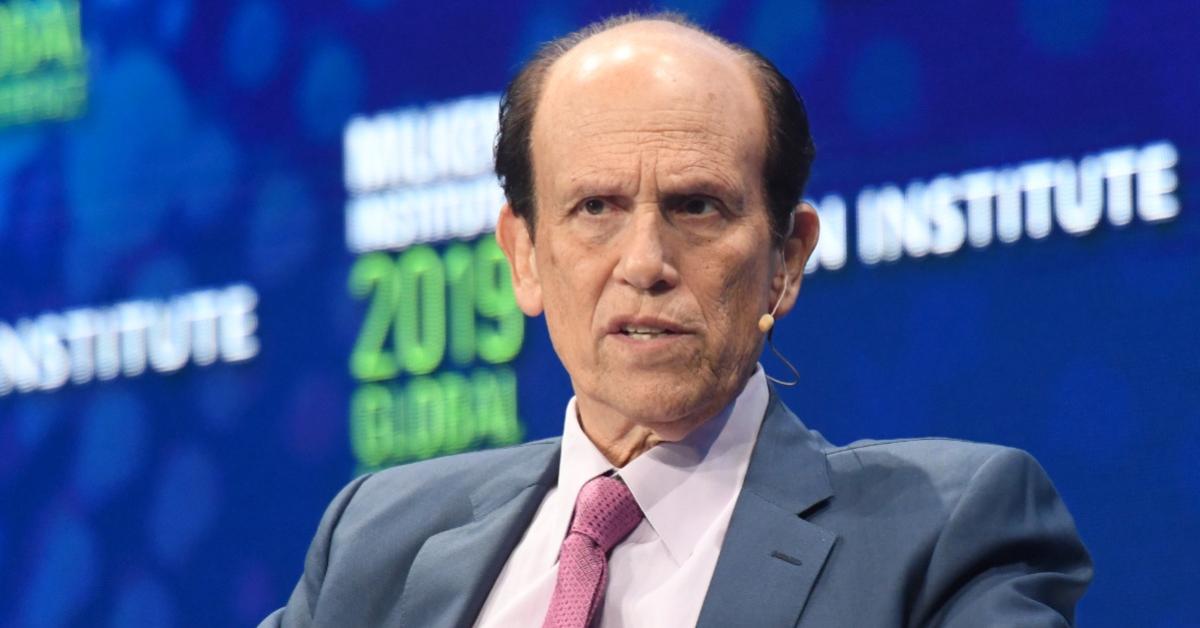

A guilt-ridden-but-not-THAT-guilt-ridden plutocrat can get helpful advice on how to create LLCs from many sources, including the California-based Milken Institute (yes, also ironically, THAT Michael Milken). The handy fact sheet notes that “(A)n LLC structure provides not only flexibility but also greater integration of various social change efforts to expedite progress . . . LLCs hybridize for-profit and charitable activities, allowing philanthropists to generate financial and social returns.” All are advantages very much tailored to accomplish the goal of building a for-profit charity.

The donors who control where the money goes are insulated from any internal or external criticism by their ability to turn off the spigot whenever they wish. In other words, don’t irk, for example, the Gates Foundation because they are going to be around forever, and your grandkid may need a job someday.

The politics of this putative philanthropy are brazened. If one looks at those who have taken the Giving Pledge, one sees a list that could easily be mistaken for a list of the owners of the private planes that jet to Davos for the annual World Economic Forum (WEF) meeting.

The WEF, it seems, could be called the hub of the many rich and important spokes in the wheel that have fundamentally changed international politics in the past twenty years. From the Great Reset pandemic response to emphasizing the growth of the social economy, the influence of the WEF and the people who support it cannot be underestimated. (Note—10 percent of the economy of the European Union is now classified as social economy or the third sector, so guess what types of entities, what stakeholders, make up the social economy.)

It should also be noted that personal direct campaign donations are also part of the overall program of sociopolitical power; though in the United States, the 537 people elected by the public to federal office are seen as mere speed bumps to be gotten around or avoided entirely (hence the growth of the regulatory and deep state and their intimate ties to the tech community).

Certain government exceptions are made, though. In the case of the sandy nations of the Middle East, the government’s money is actually theirs. And in the case of poorer leaders, all they have to do is bow down to hedge fund and NGO-driven Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) financial processes like Sri Lanka did, and then they get to sit at the big kids’ table.

In fact, the web that weaves from WEF to NGO to foundations to media to government to consultants to stakeholders to experts to the financial world to politics and back to effective altruism is both unmistakable and intentional.

Some of the moneyed meddlers do not exactly fit the above mold. George Soros, at least, is extremely up-front about using his money to buy influence, destroy the American justice system, corrupt the media, and, in general, attempt to bring down Western civilization as we know it. Soros made his money in finance, including his infamous shorting of the pound in 1992 which netted him $1 billion in a day or so, even if it came at the expense of the British people—and here’s his website.

Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) also practiced effective altruism; of course, he did it with stolen money, but he says he meant well. Bankman-Fried, however, could be seen as a mirror universe of a Soros or a Zuckerberg or Bezos or eBay’s founder Pierre Omidyar or Reed Hastings and his wife, what’s her name, all of whom really began buying global power—sorry, donating to worthy causes—only after they had actually made a ton of real money.

SBF clearly knew early on that he was going to need legal, social, political (the amount of money handed over to Democrat/woke causes is enough to make eyes water), and media protection at some point . . . and he clearly got it as he is now sitting in his (also very politically/Silicon Valley–connected) parent’s multimillion-dollar home in Palo Alto instead of rotting in a rat infested, nonvegan Bahamian jail. (It’s also clearly why he was arrested the day before he was scheduled to testify in front of Congress—nobody “on the inside” wanted that to happen, no way no sirree.)

It is the future that is at the center of this issue. The organizations and people involved talk about impact investing, data-driven giving, and using evidence and reason to plan their permanent programs.

They don’t talk about giving for today—they talk about investing in the future.

Because they don’t think it is our future. They know it is already theirs.