Government “Stimulus” Keeps Having a Diminishing Effect

The United States economy recovered at a 6.5 percent annualized rate in the second quarter of 2021, and gross domestic product (GDP) is now above the prepandemic level. This should be viewed as good news until we put it in the context of the largest fiscal and monetary stimulus in recent history.

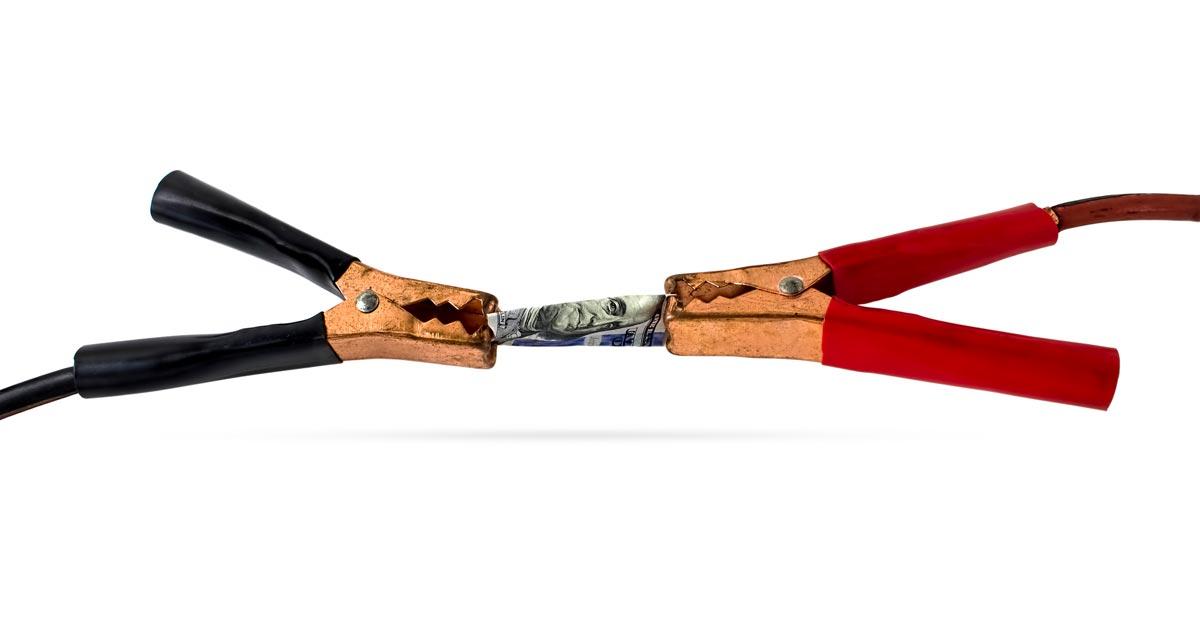

With the Federal Reserve purchasing $40 billion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and $80 billion in Treasurys every month, and the deficit expected to run above $2 trillion, one thing is clear: the diminishing effect of the stimulus is not just staggering, but the increasingly short impact of these programs is alarming.

The GDP figure is even worse considering the expectations. Wall Street expected a GDP growth of 8.5 percent and most analysts had trimmed their expectations in the past months. The vast majority of analysts were sure that real GDP would comfortably beat consensus estimates. It came in massively below.

What is wrong?

In recent times, mainstream economists only discuss the merit of stimulus plans based on the size of the programs. If it is not more than a trillion US dollars it is not even worth discussing. The government continues to announce trillion-dollar packages as if any growth at any cost were acceptable. How much is squandered, what parts are not working, and, more importantly, which ones generate negative returns on the economy are issues that are never discussed. If the eurozone grows slower than the United States, it is always blamed on an allegedly lower size of stimulus plans, even if the reality of figures shows otherwise, as the European Central Bank (ECB) balance sheet is significantly larger than the Fed’s relative to each economy’s GDP and the endless chain of fiscal stimulus plans in the eurozone is well documented.

In the United States, we should be extremely concerned about the short and diminishing impact of monster stimulus plans. Paul Ashworth at Capital Economics warned that this is more evidence that stimulus provided surprisingly little bang for its buck, and reminded people that “with the impact from the fiscal stimulus waning, surging prices weakening purchasing power, the delta variant running amok in the south and the saving rate lower than we thought, we expect GDP growth to slow to 3.5 percent annualized in the second half of this year”.

The so-called consumption boom that many expected for 2021 and 2022 after the high savings increase of the lockdowns is now more than questioned.

Real consumption probably contracted in May and June, the consensus has made downward revisions to income growth estimates, and the saving rate is estimated to have fallen to 10.9 percent in the second quarter, very close to the trend average of 9 percent.

Furthermore, residential investment contracted by 9.8 percent and federal nondefense spending contracted by 10.4 percent even with massive deficit spending.

The 0.8 percent monthly increase in headline durable orders in June was also a lot smaller than consensus had expected. Excluding transport, it was worse, at just a 0.3 percent month-on-month rise.

Additionally, inflation is eroding citizens’ purchasing power and weakening the margins of small and medium enterprises.

This, again, is the proof that neo-Keynesian “spend at any cost” policies generate a very short-term sugar rush followed by a long-term trail of debt and zombification. This disappointing 6.5 percent annualized gain in second-quarter GDP, well below the consensus at 8.5 percent, is even worse considering the monster size of the fiscal and monetary stimulus, with declines in residential investment and a bigger drag from inventories.

Something is very wrong when the US GDP is growing at 6.5 percent but salaries grow only at 3.5 percent, with inflation at 4 percent annualized and the PCE price index at 6 percent, weekly jobless claims at four hundred thousand, and continuing claims at 3.3 million. In March 2020 jobless claims were coming in at about 220,000 a week.

With these figures, it is not a surprise to see that the University of Michigan consumer confidence index has fallen to a five-month low of 80.8 in July from 85.5, driven by both the current conditions and expectations indices, with the former falling from 88.6 to 84.5 and the latter showing a slump from 83.5 to 78.4.

The 0.6 percent increase in retail sales in June was a decline in real terms, as consumer prices rose 0.9 percent. Additionally, May’s decline in headline sales was revised up to a worse figure, 1.7 percent, from 1.3 percent previously published. Is this a healthy economy? No.

The entire stimulus plan is doing nothing to improve the job recovery or the real economic improvement. The real economy collapsed due to the lockdowns and is recovering thanks to the vaccination and reopening. Almost all of those trillions of dollars spent on questionable programs are generating no real effect. We can even say that jobless claims should be half of what they are today in a normal recovery and that massive government intervention is slowing the improvement.

It cannot be denied that the government and economists need to start looking at these programs and monitoring their results, not just adding another zero to the next stimulus program and hoping for the best.

The disappointing quarter GDP is also a concern because the slowdown will likely be abrupt and leave a trail of debt that will be very difficult to reduce. However, if governments can spend all they want, they will always blame the weak results on not spending enough.

Does this mean that nothing should have been done? No. To ensure a robust recovery and lower inflation the government should have implemented supply-side measures, tax rebates, and support job creation boosting business start-ups and helping small and medium enterprises, not bloating federal programs that have nothing to do with covid-19 under the excuse of the pandemic.

This is yet more proof that you cannot print and spend your way to prosperity. The lesson is that artificially bloating GDP and inflation always hurts the economy in the long run, especially the middle classes, who suffer more the loss of purchasing power and the difficulty to save.