Egypt Is Still Haunted By Its Ghosts of Socialism

Egypt is considered a former socialist state and a country where the tentacles of Marxism can still be found, buried deep within almost every institution, something I have observed having lived there many decades. As I watch and listen to so-called leftists and socialist activists from Europe and North America preach about the need for wealth redistribution and the benign merits of Marxist ideologies, I wonder: What, exactly, are they talking about? Experience with socialism outweighs the ideologies of Marxism.

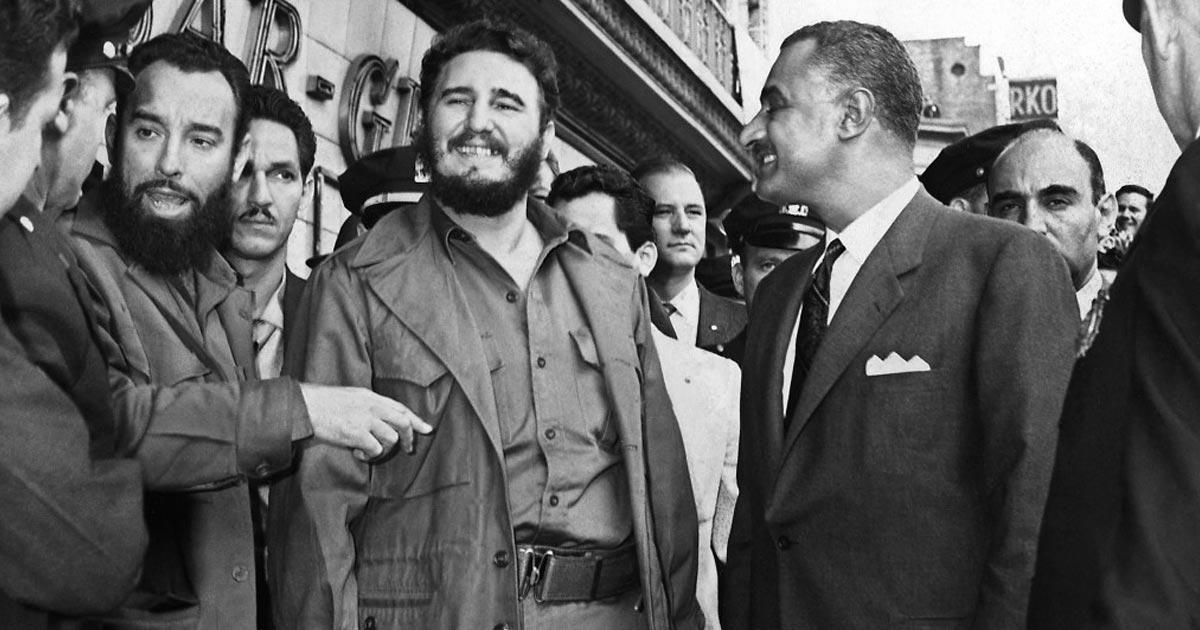

In Egypt, after the 1952 coup d’état and the overthrow of Farouk I, Egypt became a republic. Within four years, Gamal Abdel Nasser, one of the leaders of the revolution, had overthrown President Mohammed Neguib, the people’s favorite, and imprisoned him. Nasser declared himself president in 1956, and soon after, started presenting himself as the new spiritual leader of the entire Arab world, the champion of the proletariat, and the bringer of socialist justice to Egypt, which he described as “the land of the half percent,” meaning that only half a percent of the population controlled the entire wealth of the nation, an incendiary and untrue statement.

As the years wore on, Nasser’s policies became harsher and more dictatorial, with vicious treatment of the upper and middle classes, sweeping nationalization, which led to various economic problems, and the complete takeover of mass media, including establishing a censorship bureau whose sole purpose was to vet every movie and TV script before production and make sure it stayed within the guidelines suggested by Nasser and his ministers. This included deleting any mention of King Farouk, as well as depicting any member of the Pasha (the Egyptian equivalent of the British peerage or knighthood), or any upper-class person, for that matter, in a favorable light. For example, two of the most celebrated Egyptian films of the era were A Woman’s Youth, released in 1956, which is about a rich society woman who turns an innocent young peasant into a gigolo; and The Nightingale’s Prayer, released in 1959, which centers on the rape of a poor peasant girl by a rich industrialist.

During Nasser’s era, intellectuals were tried and imprisoned, and class friction poisoned society, mainly due to Nasser’s rousing speeches about the exploitation of the poor by the bourgeois. Fear and paranoia pervaded everyday life, as citizens dreaded the visits from the Salah Nasr patrol, or “The Dawn Patrol,” agents of the state who arrested dissidents at dawn. Those arrested would be imprisoned and tortured, and some disappeared altogether. Over time, it became clear to many that Nasser’s idol was Joseph Stalin, whose playbook Nasser openly admired. While there were no gulags nor sweeping genocide in Egypt, there was terror, ruthlessness, and borderline fascism, things Egypt had not experienced before, not even under the most brutal of colonial regimes.

More than fifty years after the death of Nasser and the fall of his socialist regime, Egypt is still haunted by the ghosts of socialism. Even today, Nasser remains the most revered of Egypt’s former presidents. Protesters at the 2011 revolution carried large posters of Nasser, and the term “Nasserist” is still being used today in lieu of the term “socialist.” The ideas that Nasser popularized and institutionalized in 1956, mainly that the wealthy and the imperialists are solely to blame for Egypt’s ills and that socialism is the answer to all socioeconomic problems, remain popular to this day, especially among youths of all classes. This has resulted in a society that is mired in bureaucracy, class resentment, and a destructive resistance to change and innovation.

Since the 2011 revolution, class envy has risen dramatically in Egypt. Pop songs make fun of the rich, and TV showrunners are back to old Nasserist tricks, with stories about the abused working class, and the exploitative bourgeois. This is not surprising, since a large portion of the programming being produced in the Arab world today comes from production companies based in Dubai, a country whose elite is almost exclusively educated in private international universities, which are supervised by radical leftist professors from Britain, the United States, and Canada. The publishing arm of the American University in Cairo, the AUC Press, has published a number of books about Nasser, almost all of them hagiographies, like Nasser’s Blessed Movement (2017). There is not, however, a single volume about President Anwar Sadat’s achievements.

Once the seeds of socialism are sowed, it’s very hard to get rid of their poisonous fruits, even after many decades. Like Sadat once said about post-Nasser Egypt, “Nasser has left me a legacy of resentment so big, I still can’t find a way to deal with it.” And fifty-plus years after Nasser’s death, Egypt still can’t find a way to deal with his destructive legacy.