Germany’s Inflation Tax and the Rising Cost of Living

Since the introduction of the euro, officially measured consumer price inflation in Germany has not made any great leaps. It has averaged 1.5 percent per year. It reached its highest value in 2008 at 2.8 percent and its lowest value just one year later at only 0.2 percent. In 2020, it has been negative for certain months but was 0.4 percent for the entire year. Do these figures provide a representative picture of the general price trends?

It is not surprising that the answer to this question remains controversial, because price inflation measurements are used to make subjective variables of economic life appear objective. How does the standard of living of citizens change? How much higher is real income today compared to twenty years ago? How much more expensive is a basket of goods of the same quality in one year compared to another? But just what equal quality even means in the course of technological progress and innovation cannot be determined objectively. Therefore, this question will never be answered conclusively.

However, there are also gaps in the official measurement of price inflation, and these can be determined without subjective value judgments. The Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), by whose trajectory much of the ECB’s monetary policy is justified, is an index for current consumption. It therefore essentially focuses on consumer goods prices and systematically excludes the prices of capital goods and future goods. Using the HICP to assess the overall standard of living thus reduces citizens to mere consumers in the present. But they are more than that.

Each individual has a more or less developed strategy to plan and make provisions for the future. People are not only consumers in the present moment, but also savers and investors who plan for future consumption (their own or others’). Quality of life is therefore determined not only by how much I can consume today, but also by how well I can provide for tomorrow. This is why price inflation for capital goods and assets is important. However, the HICP does not take it into account.

Moreover, the general tax burden is important. It makes both present consumption and providing for the future more difficult. “Public goods,” such as education, health, infrastructure, environmental protection, and law and order, that are financed by taxes in turn have an impact on the general standard of living. Here, too, the general trend in quality cannot be determined objectively. For some, the quality of public goods has declined; for others, it has not. What can be objectively determined here, however, is the monetary price that citizens have to pay for them. It can be quantified by the total tax burden.

Taking into account both assets in the form of stocks (DAX) and residential property (index calculated by the Bundesbank), as well as the price of public goods in the form of total tax revenues, yields substantially higher inflation rates for Germany since the introduction of the euro.1 The question is how much weight to assign to the individual components in order to calculate an alternative index. Again, there is no objectively correct answer. Hence, the alternative index presented below makes no claim to general validity.

According to the OECD, the average total tax burden of a German household is about 40 percent of gross income. Therefore, a weight of 40 percent for total tax revenue is plausible.

Many households spend a substantial share of their gross income on the purchase of a residential property over a long period of time. Therefore, the Bundesbank’s residential real estate index is assigned a weight of 15 percent. The DAX is given a weight of 10 percent to reflect investment in stocks. The HICP makes up the remainder of the alternative index with a weight of 35 percent. The following table shows the average annual inflation rates of the individual components and of the calculated alternative index.

Table 1: Average Annual Inflation Rates in Germany

|

Period |

HICP |

Residential property |

DAX |

Tax revenue |

Alternative index |

|

1999–2019 |

1.49% |

1.92% |

4.75% |

2.97% |

2.57% |

|

2010–2019 |

1.42% |

4.20% |

8.32% |

4.01% |

3.74% |

The alternative index has risen by an average of almost 1.1 percentage points faster than the HICP per year since 1999. This divide has increased over the past ten years with the advent of unconventional monetary policy. Since 2010, officially measured price inflation has been about 2.3 percentage points below the calculated alternative measure. What does this mean for an average household living primarily on labor income?

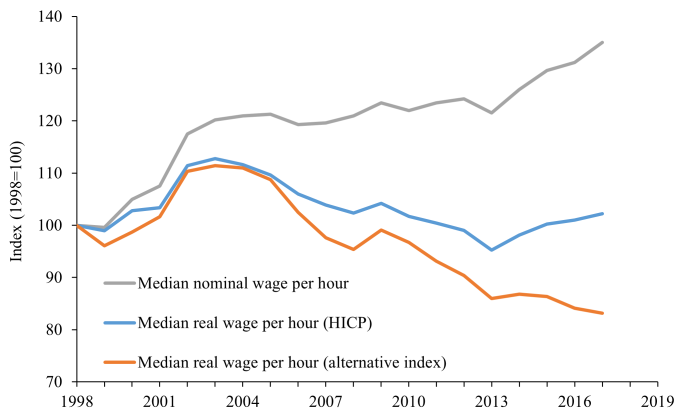

Figure 1: Median Nominal and Real Wages in Germany

The median nominal gross wage per hour increased by 1.59 percent per year between 1999 and 2017, according to data from the Socio-Economic Panel of the German Institute for Economic Research. If the HICP is used to calculate real wages, real wage growth is still positive, but only at a sobering rate of 0.12 percent per year.

However, if we use the alternative inflation measure, real wages fell by 0.97 percent per year between 1999 and 2017. Between 2010 and 2017, the average annual growth rate of real wages was even –2.17 percent. This means that the median wage per hour in 2017 still had about 83 percent of the real purchasing power of the median wage in 1998. On average, people can buy less from their working wages when more than just the goods of everyday consumption are taken into account.

This result is due to disproportionate asset price inflation and a rising tax burden, which of course affect different households differently. Households that live almost exclusively on labor income and have no real assets, but try to build up real savings for the future, suffer from this development. Young families in particular, which cannot count on the material support of their parents’ and grandparents’ generation, are finding it more difficult to establish a comfortable economic existence. The anxiety and existential fears of the average German household, which one hears about more and more frequently, are not surprising in light of disproportionate asset price inflation. With a broader look at price inflation, it becomes clear that real labor income of the citizens has been devalued substantially beyond direct taxation. Households that cannot increase their income through capital gains are the first to suffer.

- 1. For more details see Karl-Friedrich Israel and Gunther Schnabl, “Alternative Measures of Price Inflation and the Perception of Real Income in Germany” (CESifo Working Paper 8583, Oct. 2, 2020).